Titus Groan, Mervyn Peake, Stuart Hall

- Kitty Liu

- Aug 21, 2022

- 7 min read

I slate this book for the first 1000 words, and then become maybe a little insightful in the next 600.

I don’t always understand what I read, and I don’t always respect what I don’t understand, but it’s rare for my only reaction to a book to be What the FUCK. As in, I do not understand why one would commend it, at all. – Coming to you live at 11:30pm, halfway through Titus Groan by Mervyn Peake.

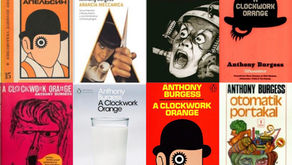

I picked up this book in the fantasy section at Waterstones, because the cover was pretty, and because ‘Titus Groan’ and ‘Mervyn Peake’ were styled in the exact same typeface so that it was impossible to tell who had written whom. I bought it because the blurb calls it ‘one of the most astonishingly sustained flights of the imagination in modern English fiction’. On the Goodreads rating breakdown, 5 stars was the most common rating, followed by 4, followed by 3, followed by 2, followed by 1. People who like Titus Groan like it with a deep and yearning fervour. Anthony Burgess calls it ‘uniquely brilliant’; Neil Gaiman and Christopher Paolini hail it as a major influence.

Titus Groan, the first novel in the Gormenghast series (three main novels published 1946-1959), is set in the castle of Gormenghast, where Titus is its 77th ruling Earl of Groan. Titus Groan begins with Titus’ birth, and follows the lives and intrigues of various other in habitants of Gormenghast and its surrounds in the period of Titus’ early infancy. The novel is not really about Titus other than that his birth sets in motion many of the book’s plot lines, although Wikipedia tells me that the second and third books are more directly about him.

The book follows a multitude of characters, an assortment of Dickensian oddities called things like Flay, Prunesquallor, Sourdust, and Sepulchrave. Each of them is mad, monomaniacal, and strange. Each of them is existentially lonely, perennially love-starved, and necessarily enmeshed in the rivalries and power struggles in the rigid and ritualistic society that is Gormenghast. This is the time to point out that Titus Groan is not a dragons-sorcerers-elves-good-vs-evil fantasy, but rather a ‘fantasy of manners’, which are fantastical explorations of characters navigating elaborate and oppressive social structures. – In this light, having an ensemble cast of grotesque characters is kind of the point, but I find the characters in Titus Groan too querulous to dispel disgust or sustain interest. Not to mention that the whole existence of Gormenghast feels inescapably tragic if you think about it too hard.

The stories of these diverse individuals unfold and interweave over the course of the book, proceeding chronologically from the day of Titus’ birth. For all its twisted and fantastical nature, I find it a somehow superficial and lacklustre story. Each character’s actions are driven by one defining motive or character trait; while these interact in often quite clever ways, they don’t particularly inspire reflection or even investment. Both the crucial and the trivial are expounded with such excruciating verbosity (more on this below) that one wonders if any of it is important. This gives an effect of such profound narrative ambivalence that you wonder why you’re being told any of this in the first place, and your only impetus to keep caring is your knowledge that you and Titus Groan are in a social contract where it is obliged to be telling you a story. The fact that the book has a third person omniscient narrator doesn’t help, since it positions the narrative as objective and impartial, thereby leaving you little interpretive license for what’s going on. Overall, Titus Groan is a book that gives you no way to engage with it except in the most literal terms. I struggle to find depth in the characters or the plot, and am rather bored by both.

The book’s structure is similarly impassive. The chapters stop and start with such ambivalence that the only way I can describe them is ‘dutiful’, as though their main purpose is classificatory rather than structural or narratological. Chapters observe unity of location more than of action or theme, and we flit between different point-of-view characters whose paths unfold and intersect roughly chronologically. It was actually weirdly refreshing to read something so structurally guileless. I don’t know why or how, but by about Chapter 4 one can simply tell that this the kind of book that’s just telling a story, and does not intend by its sheer formal existence to comment on the nature of narratology and Western intellectualism. Maybe this says more about me than it does about the book, but for present purposes, the straightforwardness of the narrative structure only compounds my impression that Titus Groan has very little going for it.

I’m also not a fan of the book’s prose. Every Goodreads review of Titus Groan that I’ve come across, even the unfavourable, comments on the richness and picturesque quality of Peake’s prose. Many call it poetic. So maybe take it with a pinch of salt when I tell you that I was really not impressed. Peake writes with an incredible wealth of detail, but he packs way too much into every sentence. Long sentences are not an issue, but it is an issue how Peake conjoins so many clauses and bits of information, that you forget the start of the sentence long before you get to its end. Obviously, not every sentence is like this, but there are enough of them to make them a stylistic feature. To quote a few:

The rook had been sitting fringed on all sides with the ivy leaves, with his head now on one side, now on the other; listening or appearing to listen with great interest and a certain show of embarrassment, for from the movement that showed itself in the ivy leaves from time to time, the white rook was evidently shifting from foot to foot. (p. 45, 1998 Vintage paperback edition)

Swelter, as soon as he saw who it was, stopped dead, and across his face little billows of flesh ran swiftly here and there until, as though they had determined to adhere to the same impulse, they swept up into both oceans of soft cheek, leaving between them a vacuum, a gaping segment like a slice cut from a melon. (p. 90)

Noting the angle of the moon and judging the time, to his own annoyance, to be hours earlier than he had hoped, Steerpike, glancing above him, could not help but notice how it seemed as though the clouds had ceased to move, and how, instead, the cluster of the stars and the thin moon had been set in motion and were skidding obliquely across the sky. (p. 120)

One could say the oppressiveness of Peake’s prose mimics the oppressiveness of Gormenghast, but I just don’t think this is good writing, let alone ‘poetic’. As a rule I love maximalist writing (cf. the other books I review on this blog), but Peake’s maximalism feels cluttered and overwrought, where quantity obscures quality and form obscures content.

Even after all this, I still wouldn’t give Titus Groan 3 out of 5 stars, or 2, or 1. This book elicits so little emotional and intellectual response from me that it doesn’t even make sense for me to call it a ‘bad book’: I’m more just confused. Which is really the crux of why I find this an interesting enough reading experience write about:

I am bored / bemused / generally unimpressed with Titus Groan because I find it uninterpretable.

The entirety of my education and media consumption has taught me that to engage with art – or media in general – is to engage with a system of allusion and interpretation. The creator encodes, the audience decodes, and they share in a semiotic system whose interlinkages are overwhelmingly predetermined by the history of the medium. It’s why a big black hat in the background of a portrait of a 17th century gentleman means he’s a Protestant; why major keys are happy and minor keys are sad; why if I see something in comic sans I can assume it’s probably a meme; and why in traditional Chinese poetry willows mean the sadness of parting, peonies mean prosperity, and a pair of carp mean letters from afar…

More to the point, this is what gives us tools like themes, tropes, archetypes, genres, dominant vs oppositional readings, etc, through which we interpret Western literature as conveying more than its literal content. If a work invokes one of these established abstractions, then we interpret it as an example thereof: Wuthering Heights is interpreted as a novel about discrimination and cruelty, esoteric art book Codex Seraphinianus as an encyclopaedia, etc etc. If not, we rationalise it in relation to how it ‘subverts’, ‘deconstructs’, ’comments on’, ‘is in dialogue with’ these categories – e.g. My Year of Rest and Relaxation as a deconstruction of idealised female characters in mainstream media, Infinite Jest as a novel that takes 1000 pages to say that communication is impossible, etc etc. When I say I find Titus Groan to be lacking in depth, I think what I actually mean is that I fail to apply to it any of these analytical abstractions from my habitual interpretive toolbox. Its characters do not relate to archetypes, its plot does not illuminate themes, its structure does not signpost it as part of any literary movement.

The other way to frame this is: Titus Groan is resolutely itself and itself only.

I also found this sentiment voiced in one of the Goodreads reviews I read. I disagree with some parts of the review (for a start, it really likes Titus Groan), but this section does hit the nail on the head:

[The characters] are stylised and symbolic, but … Peake is working off of his own system of symbology instead of relying on the staid, familiar archetypes of literature. … In the introduction [to Titus Groan], Quentin Crisp tells us about the nature of the iconoclast: that being different is not a matter of avoiding and rejecting what others do – that is merely contrariness, not creativity. To be original means finding an inspiration that is your own and following it through to the bitter end. (J G Keely, 2009)

I think I will leave it here. I don’t tend to review books before I’ve finished reading them; but then I don’t tend to stop halfway through a book to ask Goodreads if I’m missing something. When I started on this review, I was undecided re whether I should finish Titus Groan. Having sifted through and reified my thoughts on the book through the sheer act of writing, I don’t think so. It’s probably just as fine a book as its Goodreads aficionados claim it to be, even if I don’t find it so. But, asides from this curious and instructive detour into reception theory, there’s nothing for me here.

留言