Italo Calvino's If on a winter's night a traveller

- Kitty Liu

- Jul 5, 2020

- 5 min read

Updated: Apr 28, 2021

In three words: freakishly mind-bending.

Prose: dense.

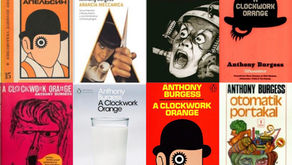

Cover art: for the Vintage Classics paperback, artless.

First thought upon finishing, at 11:15pm on a Wednesday night: why do I subject myself to reading books like this?

Would recommend? Would recommend.

This is a very clever book. Everyone who’s ever talked about it has probably said so already, and now I’ve said it too: this book is very clever.

A Reader starts reading a book but finds that his copy is faulty. He tries to obtain a complete copy, but ends up being given a different book. When he finds that this book is also incomplete, he tries to track it down but is presented with another new unfinished book: this repeats ad nauseum. The Reader is joined by a woman named Ludmilla (‘the Other Reader’), and his quest to track down the unfinished books leads him to, among other things, an academic dispute over the nationality of an author, an ailing publishing agency, a fraudulent translator, and the censorship bureau of an authoritarian state. Oh, and the book is narrated in the second person, so the Reader is officially ‘you’. ‘You’ buy a book, ‘you’ go to a literature seminar, ‘you’ read a translator’s spurious correspondence, ‘you’ are captured by the police in South America…

Because ‘you’ spend the book reading the beginnings to all the novels ‘you’ get given, so do you: the plot of the book is interspersed with openings of the interrupted novels, framing them. Every other chapter of the book is the incipit of another novel, while the remaining chapters tell the story of ‘your’ quest. The incipits suggest novels of varying genre and style; the quest narrative begins with a cosy realism that devolves into absurdist satire.

I really liked the structure, especially as the book’s ending proved strong enough for a satisfactory tie-off. I personally found the incipits hard to get into, as it can take three or four pages of verbose drudgery before the new fictional landscape starts to make sense, or any characters become tangible. I realise the constant relocation is a key feature of the book, but it does feel a little heavy-handed.

The second person narrative is a highlight. This is the first second-person novel I’ve read, and it’s so effective at drawing you in that I don’t know why writers don’t use it more. The first pages of the book describes ‘you’ picking up the first book at the bookshop (which also happens to be If on a winter’s night a traveller by Italo Calvino - the book’s self-reference, and the abundance of books and readers in it, makes it hard to even talk about it clearly) and settling down at home to read it. Calvino taps into experiences readers can all relate to, and his use of the imperative really brings it home:

Find the most comfortable position: seated, stretched out, curled up, or lying flat. Flat on your back, on your side, on your stomach. In an easy chair, on the sofa, in the rocker, the desk chair, on the hassock. In the hammock, if you have a hammock. On top of your bed, of course, or in the bed. You can even stand on your hands, head down, in the yoga position. With the book upside down, naturally.

It’s so personal. It sounds like a guided meditation by Dr. Seuss, and I almost feel the impulse to ‘delete as appropriate’ from among these choices.

Some people go so far as to say, mistakenly, that you, the actual reader, are the protagonist of If on. But really Calvino is talking to ‘you’, the Reader with the capital R, with whom you are encouraged to identify at the start of the book. ‘You’ is no more the reader than the ‘I’ in a first person novel is the author. The place of ‘I’ in a second-person book is explored in the first incipit, a first-person spy novel. The main characters in the chapter are ‘me’ and ‘you’, the narrator and the Reader, where ‘I’ am always pointing out the author’s decisions for the content of ‘my’ narration, and how this manipulates ‘your’ attention.

The Reader’s character becomes more defined as the book progresses, to show a rather guileless young man motivated partly by an exasperated curiosity about the incomplete novels, and partly by his desire to impress the Other Reader Ludmilla. Yet because the Reader is identified as ‘you’, you continue to project his thoughts and feelings onto yourself in a much more personal way than if the story was narrated in the first or third person.

The Reader’s quest for the complete novels leads him to meet a variety characters to whom books are important. Each of these characters have a particular way of relating to books, as readers or as participants in the publishing industry. None of them really have much depth as characters, but in a sense that’s beside the point. They are there as personifications for different ways in which people can relate to books. For Ludmilla, books offer the pleasure of experiencing without thinking. She makes a point of distancing herself from the publishing industry, to protect the innocence of this pleasure. For her sister, books are simply amalgamations of words, demanding objective analysis for their reflections of social codes. One of their friends sees literacy as an entrapment: he has un-learned how to read, and now appreciates books only for their aesthetic value as physical objects. A writer suffering writer’s block feels alienated from his productive self, while a tech company has succeeded in machine-producing novels after his style. A secret organisation steals manuscripts to protect the novels that reflect the universal Truth, while its rival organisation denies the existence of such a Truth, but steals manuscripts to proclaim mystification and falsehood…

The Reader just wants to read a good book from start to finish, and mutely perceives the other characters’ conviction. At the end of the book, the Reader encounters an ensemble of readers at the library, who suggest a different approach to reading. For the earlier characters, the focus of all interactions with books, be it reading, publishing or writing, is always the book itself: be it an experience, a code, a piece of divine inspiration or a vessel for truth, the book is always an absolute object, ultimately detached from its spectators.

For the readers at the library, reading isn’t about the objective book, but the subjective experience of reading. One reader likes the possibility of beginnings, another the resonance of endings. One reader says that each time they read the same book it’s a different experience because of their different points of focus. For another reader every book they read adds to the continuum of their life’s readings. What reading means to each of them is different, but they are all content with recognising and enjoying it, whereas the earlier characters are so fixated on what they think a book is that they neglect their relationship with it.

Comments