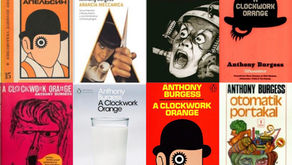

Anthony Burgess' A Clockwork Orange

- Kitty Liu

- Jul 13, 2020

- 10 min read

Updated: Apr 22, 2022

I talk about the semantics and sociolinguistics of the novel's constructed slang language for 2000 words. Then I give strong opinions about the book's ending. Spoilers, I suppose.

Anthony Burgess’ A Clockwork Orange is probably the most violent thing I’ve ever read, but I love it. It’s so horrific and exhilarating that when I first read it in November 2019, I immediately went back and read it again.

It’s a story about Alex, a teenaged delinquent who likes ultra-violence and classical music. When he kills a woman during a gang robbery, he is imprisoned and undergoes aversion therapy, where he is conditioned to associate violence with the nauseating effects of a drug. In terms of genre, it’s dystopian sci-fi, darkly satirical. Thematically, a philosophical story about free will: is it really better to be coerced into goodness, than have the freedom to choose evil? (Or, depending on how you interpret the ending, it could also say that individual choice cannot change the general prevalence of evil.)

But for me, the best thing about this novel is its linguistic landscape. Alex narrates the story in the slang spoken by street toughs, paratextually referred to as Nadsat. In the book Alex calls it ‘nadsat talk’, and ‘nadsats were what we used to call the teens’.

Learning Alex’s Language

A Clockwork Orange begins like this:

‘What’s it going to be then, eh?’

There was me, that is Alex, and my three droogs, that is Pete, Georgie, and Dim, Dim being really dim, and we sat in the Korova Milkbar making up our rassoodocks what to do with the evening, a flip dark chill winter bastard though dry. The Korova Milkbar was a milk-plus mesto, and you may, O my brothers, have forgotten what these mestos were like, things changing so skorry these days and everybody very quick to forget, newspapers not being read much neither. Well, what they sold there was milk plus something else. They had no licence for selling liquor, but there was no law yet against prodding some of the new veshches which they used to put into the old moloko, so you could peet it with vellocet or synthemesc or drencrom or one or two other veshches which would give you a nice quiet horrorshow fifteen minutes admiring Bog And All His Holy Angels and Saints in your left shoe with lights bursting all over your mozg.

You may start off in complete bewilderment on the first page, but you pick up Nadsat as you go along. Burgess himself likened this process to ‘brainwashing’, so insidiously easy it is to pick up Nadsat as you read the story. This is by far what excites me most about this book: essentially, it’s empirical proof for Wittgenstein’s dictum meaning is use. Before you read A Clockwork Orange, Nadsat words are non-words. But they become meaningful to you as you read, simply through Burgess / Alex using them in context, until by the end you can understand things like ‘the starry chelloveck razrez his platties’.

You can tell the meaning of some Nadsat words from a single occurrence, like in ‘making up our rassoodocks what to do’ at the start of a gang meet-up, or a ‘well-oiled pooshka, complete with six dirty rounds’ during a fight. Others, from a few. From ‘starry grey-haired ptitsa’, ‘starry oldie’, and ‘doddery starry schoolmaster’, you get a sense that ‘starry’ probably has to do with being old. For words that appear in less strategic contexts, Alex gives a parenthetical explanation: ‘[codpiece in the shape of] a rooker (a hand, that is)’, ‘in Staja (State Jail, that is)’.

Interestingly, it’s possible to guess a word’s meaning, have your conclusion fit the available evidence from the novel, but be proven wrong by paratextual information. Take ‘malenky’. It’s an Anglicised Russian word, but I’m in the dark because I don’t know any Russian. Alex uses it a lot, in conjunction with a diverse range of things, such as ‘malenky jest’, ‘malenky cottage’, ‘a malenky bit too slow’, ‘a malenky man, very fat’, ‘malenky [boy], no more than about six years old’. Context doesn’t offer as much help for adjectives and adverbs as it does a noun or a verb, and I couldn’t come up with a single English word to fit all these collocations. I gravitated towards thinking that ‘malenky’ might be like ‘great’ or ‘greatly’ in normal English, which essentially indicates abundance of size or significance (‘a great crowd’, ‘great historical events’) but is often used to show an abundance of good (‘great book’, ‘great friend’ etc). So for the phrases containing ‘malenky’, it would be ‘nice jest’, ‘nice cottage’, ‘way too slow’, ‘big man’, ‘lusty boy’, and so on. But ‘malenky’ is supposed to mean ‘little’, since it comes from маленький, Russian for ‘small’. ‘Malenky’ meaning ‘little’ does fit the evidence better: it always works to substitute ‘little’ for ‘malenky’, whereas for ‘malenky’ meaning ‘great’, you have to use a variety of synonyms. Yet the latter is still an internally consistent interpretation when you consider the text alone.

For some words, the narrative doesn’t provide you with enough information to figure out what exactly it means, but its presence is still effective. In a scene where Alex rapes two younger girls, ‘the strange and weird desires of Alexander the Large’ are described as ‘choonessny and zammechat and very demanding’. Without any Russian, it’s impossible to figure out the exact meanings of ‘choodessny’ and ‘zammechat’ from the novel, as this is the only time where they appear. But your not knowing their meaning doesn’t detract from the horror of the scene - rather the horror is heightened as you shudder and feel you’d rather not know what Alex is thinking. Alternatively, there are words like ‘grahzny’ that appear a lot (e.g. ‘grahzny bastards’, ‘greasy and grahzny glass’), but not enough for you to supply a definitive English equivalent. But unlike the more ambiguous ‘malenky’, you can clearly tell that ‘grahzny’ is negative if not derogatory. After seeing it a few times, you learn to appreciate the sentiment behind it despite not knowing its dictionary definition.

I’m making these comments as someone who knows neither Russian nor any other Slavic language. When I read A Clockwork Orange, I am acquiring Russian-derived Nadsat words from scratch, without any prior knowledge of what their roots might mean. I imagine that for people who know Russian, reading this book is a very different linguistic experience. (If you know Russian or any other Slavic language, and have read A Clockwork Orange, please let me know as I’d be very interested to hear about your experience. I might as well treat this blog of mine as the quasi-public platform that it is.)

Publishers tend to print A Clockwork Orange with a Nadsat glossary, although Burgess was was openly opposed to it. Readers of A Clockwork Orange do often cite Nadsat as a stumbling block, saying that always flipping back to the glossary adds to the confusion and disrupts the flow of the story. Nadsat itself is often framed as the source of bad reading experiences, but I think the problem rather comes from having a glossary to lean on. The first few chapters are daunting, but they should be: you are thrown into Alex’s world at the deep end, and getting used to the language is like adjusting to any other aspect of a new fictional world. We pick up Nadsat words in the exact same way we pick up unfamiliar English words, by hearing or seeing them in context. Both following the narrative and acquiring Nadsat rely on you hanging on to the flow of Alex’s narrative, and not getting hung up on unfamiliar vocabulary.

(Obviously I didn’t use a glossary when I read the book - no the contrary I compiled one myself, to show that acquiring Nadsat is completely possible, that meaning can be derived from use.)

(Sidenote, Jan. 2021: The opening passage from A Clockwork Orange shows up as the opening exercise in Farmer & Dermers (2001) A Linguistics Workbook (4th ed.), that one of my lecturers kindly shared with us. I feel so vindicated.)

Nadsat Lives in a Society

Burgess achieves a lot of world-building through Nadsat. Language, how it’s used and how it’s perceived, throw light on the workings of Alex’s world and sets the story’s prevailing tone.

In this dystopian novel that isn’t directly about the dystopia, Nadsat functions as a window into its underlying socio-political landscape. Nadsat vocabulary is predominantly made up of Russian loanwords (a result of ‘propaganda, subliminal penetration’) and Cockney rhyming slang, plus influences from Elizabethan English, Romani, English street slang, Malay, and baby-talk. Burgess leaves you to wonder what kind of global politics led to Nadsat’s formation, but leaves the exact aetiologies to the reader’s imagination.

The speakership of Nadsat illuminates how Alex and his ilk fit into broader society. Nadsat is only spoken by Alex’s age-group, i.e. the mid-teens: the ten year-old girls Alex meets have their own ‘weird slovos that were the heighth of fashion in that youth group’; in prison, he doesn’t know the slang of the adult criminals. Nadsat is definitely not spoken by respectable society. When his post-corrective social worker visits, Alex’s attempt to break from Nadsat (‘A cup of the old chai? Tea, I mean … brother, sir I mean’) mirrors his false assertion that he’s a good boy now. Later, Alex is horrified to find that his ex-droog Pete has got married and entered into law-abiding society, where they talk in ‘a grown-up goloss’ and think Alex ‘talks funny’. This moment shatters Alex’s perception of himself, reflecting how tightly Nadsat is tied to his identity: in the Us vs Them attitude of teenage gangs, Nadsat previously embodied a solidarity between all of Us, and now it marks out Alex as society’s Them. But people like Alex have always been society’s Them: a government doctor calls Nadsat ‘quaint, a dialect of the tribe’ with an offhand contempt: brutal thugs as they are, the speakers of Nadsat are ultimately powerless and insignificant.

Nadsat is also crucial to establishing the tonal setting of Alex’s world, which is far more pervasive and evocative than its socio-political structures. The appropriation of words from Russian and rhyming slang etc introduces atypical sounds, spellings and semantic connotations that clash with the standard English we are familiar with. Unheard-of words (‘kartoffel’, ‘peet’, ‘glazzies’), un-English consonant clusters (‘mozg’, ‘devotchka’, ‘veshch’), English-looking slang you should probably know (‘gulliver’, ‘twenty-to-one’, ‘Aristotle’)… Alex also uses a lot of onomatopoeia, from a door opening ‘squeeeeeeeeeek’ to blowing a raspberry, ‘lip-music - Prrrrzzzzrrrr’, to a brutalised old man making ‘sort of chumbling shooms - ‘wuf waf wuf’ ’. Auditory vividness is complemented by the visual, an incessant but blurred stream of graphic violence, out of focus because you still don’t know half the words.

There is distinct humour in Alex’s speech. A lot of Nadsat words are funny, like ‘Bog’ for ‘God’, or ‘rabbitting’ for ‘working’. It also blends archaisms like ‘O my brothers’ and ‘gloopy bastard as thou art’ with childish tics like ‘eggiweg’ for ‘egg’ and ‘appy polly loggies’ for ‘apologies’. When Alex talks to adults in non-Nadsat, it sounds like a parody of normal speech: ‘Yum yum, mum, any of that for me?’, or ‘[go back] to my parents in the dear old flatblock’. Quite often Alex leans into the ironical, whether establishing his relationship with the reader (‘Your Humble Narrator’), or recounting how his machinations were his downfall (‘I played with great care, the greatest, saying, smiling’). Self-awareness and humour make him more sympathetic as a character, but in the grander scheme of things they hardly temper his heinous sadism.

The content of Alex’s narrative show a violent and ugly world. Yet its medium, the language, is just as effective at conveying chaos and cacophony. Nadsat - its usage, its throwaway to wryness, the hints at its history - gives more depth to Alex’s world, showing that it is sardonic and precarious as well as twisted.

Emotional Manipulation

Nadsat plays with the emotional distance between Alex and the reader. By partaking in Alex’s language, we are invited to see the world through his eyes, with his sympathies. Alex’s wide array of derogatory labels are, like all insults when used with conviction, self-justifying: if there is nothing wrong with that man, Alex wouldn’t be calling him a lewdie; lewdies are worthy of contempt, so it must be okay to hit the man. That is, until you realise a lewdie describes anyone who isn’t part of Alex or his rivals’ gangs, i.e. a normal person.

The reader’s initial lack of familiarity with Alex’s vocabulary also takes the edge off the senseless violence. For the first few chapters, you are in a blur where you feel Alex and his droogs are beating random people up, but you aren’t quite sure what exactly is going on. A few chapters later, you know on an intellectual level that Alex giving a ‘tolchock on the gulliver’ to a ‘starry farella’ means Alex smashes at an old lady’s head, but because you are still unused to associating these new Nadsat words with their referents, you have less of a visceral reaction to the scene. Now I wince on every other page when I read the book’s Part One, but the first time I read it, I sat through the atrocities with a surreal detachment.

As the book progresses, we do become more adept at understanding Nadsat and giving appropriate emotional responses. However, only in the first Part does Alex perpetrate any significant, unprovoked violence. In the latter Parts, Alex turns from the victimiser into the victimised, so our better understanding of Nadsat’s vocabulary for violence in fact helps us to sympathise with Alex. In this novel pain literally feels more real when Alex is on the receiving end.

The Ending: a Vindication

Now that I’ve recounted my thoughts on A Clockwork Orange as a linguistics nerd, I’d like to talk about the novel’s ending.

In the penultimate chapter, Alex’s anti-violence conditioning is undone and he regains his appetite for violence. The last chapter sees Alex resuming his old life with some new droogs and the old ultra-violence, but soon Alex tires of it and contemplates rejecting crime and settling down to start a family. Burgess himself apparently envisioned it as a happy ending: Alex renouncing violence of his own accord is truly the best of both worlds, so he can simultaneously be good and exercise his free will. This final chapter was cut from the book’s American publication and the subsequent Kubrik film: having Alex return to his violent tendencies with relish seemed more in keeping with the book’s dystopian tone.

I disagree.

For me, that excised ending is what makes the book truly horrific. The contrast between the extent of Alex’s ultra-violence and the ease with which he grows out of it is disturbing. One gets the impression that Alex is completely desensitised to violence, and rejects it because it feels unsatisfying, not because it’s bad. Although Alex personally renounces violence, the immutability of violence is reinstated on a bigger scale. In this last chapter, we see that gang members and fashion trends come and go, but the existence of teenage thugs is a constant in Alex world. As Alex envisions family life, and if his son will make the same mistakes, one wonders if Alex’s staid father was once also a thug like him, and whether Alex’s son will definitely become one. This cyclicality cements the true dystopia, not a moral one but a structural one, not rooted in Alex’ being personally irredeemable but in how violence is completely entrenched in this society. Years pass, individuals grow up, slang changes, but ultra-violence will grip generation after generation.

Comments